Scientific research is maturing in a number of developing nations, which are trying to join North American and European nations as recognized centres of research. As recent stories show, the pressure to fulfill this vision--and to publish in English-language, international journals--has led to some large-scale schemes to commit academic fraud, in addition to cases of run-of-the-mill academic dishonesty.

In China, a widely-discussed incident involved criminals with a sideline in the production of fake journal articles, and even fake versions of existing medical journals in which authors could buy slots for their articles. China has been criticized for widespread academic problems for some time, for example, 2010 the New York Times published a report suggesting academic fraud (plagiarism, falsification or fabrication) was rampant in China and would hold the country back in its goal to become an important scientific contributor. In the other recent incident, four Brazilian medical journals were caught “citation stacking”, where each journal cited the other three excessively, thus avoiding notice for obvious journal self-citation, while still increasing their journal’s impact factor. These four journals were among 14 having their impact factors suspended for a year, with other possible incidences that were flagged but could not be proven involved Italian, a Chinese, and a Swiss journal.

There are some important facts that might provide context to these outbreaks of cheating. Both Brazil and China are nations where to be a successful scientist in the national system, you need to prove that you are capable of success on the world stage. This is probably a tall order in countries where scientific research has not traditionally had an international profile and most researchers do not speak English as their first language. In particular it leads to focus on values which are comparable across the globe, such as journal impact factors, as measures of success. In China, there is great pressure to publish in journals included on the Science Citation Index (SCI), a list of leading international journals. When researcher, department, and university success is quantified with impact factors and SCI publications, it becomes a numbers game, a GDP of research. Further, bonuses for publications in high caliber journals can double a poorly-paid researcher’s salary: a 2004 survey found that for nearly half of Chinese researchers, performance based pay was 50+ percent of their income. In Brazil, the government similarly emphasizes publications in Western journals as evidence of researcher quality.

It’s easy to dismiss these problems as specific to China or Brazil, and there are some aspects of the issue that are naturally country-specific. On the other hand, if you peruse Ivan Oransky’s Retraction Watch website, you’ll notice that academic dishonesty leading to article retraction is hardly restricted to researchers from developing countries. At the moment, the leading four countries in retractions due to fraud are the US, Germany, Japan, and then China, suggesting that Western science isn’t free from guilt. But in developing nations the conditions are ripe to produce fraud. Nationalistic ambition is funnelled into pressure on national scientists to succeed on the international stage; disproportionate focus on metrics of international success; high monetary rewards to otherwise poorly paid individuals for achieving these measures of success; combined with the reality that it is particularly difficult for researchers who were educated in a less competitive scientific system and who may lack English language skills, to publish in top journals. The benefits of success for these researchers are large, but the obstacles preventing their success are also huge. Combine that with a measure of success (impact factor, h-index) that is open to being gamed, and essentially relies on honesty and shared scientific principles, and it is not surprising that system fails.

Medical research was at the heart of both of these scandals, probably because the stakes (money, prestige) are high. Fortunately (or not) for ecology and evolutionary biology, the financial incentives for fraud are rather smaller, and thus organized academic fraud is probably less common. But the ingredients that seem to lead to these issues – national pressures to succeed on the world stage and difficulty in obtaining such success; combined with reliance on susceptible metrics – would threaten any field of science. And issues of language and culture are so rarely considered by English-language science (eg.), that it can be difficult for scientists from smaller countries to integrate into global academia. There are really two ways for the scientific community to respond to these issues of fraud and dishonesty – either treat these nations as second-class scientific citizens and assume their research may be unreliable, or else be available and willing to play an active role in their development. There are a number of ways the latter could happen. For example, some reputable national journals invite submissions from established international researchers to improve the visibility of their journals. In some nations (Portugal, Iceland, Czech Republic, etc), international scientists review funding proposals, so that an unbiased and external voice on the quality of work is provided. Indeed, the most hopeful fact is that top students from many developing nations attend graduate school in Europe and North America, and then return home with the knowledge and connections they gained. Obviously this is not a total solution, but we need to recognize fraud as problem affecting and interacting with all of academia, rather than solely an issue of a few problem nations.

Showing posts with label China. Show all posts

Showing posts with label China. Show all posts

Monday, September 30, 2013

Monday, April 15, 2013

Ecology goes east: research in China

with Shaopeng Li

To start with, what is the general perception of ecology in China? Is it popular as a science? How likely are undergrads to choose it as a major or postgraduate degree?

Shaopeng Li: The common people in China often treat ecology as “ecological civilization”, “environmental protection” or “sustainable development”. Few people recognize it as a science. Some people even don’t know the difference between ecologists and environmentalists. But I think most people agree that ecology and what the ecologists do are very important to the development of China and their own life, despite that they often do not know what the ecologists exactly do.

It is sad to say that ecology is one of the most unpopular areas of life sciences in China. Most of undergrads in life sciences want to get a Master or PhD degree in molecular biology, pharmacy or environmental technology, which is easier to find a suitable job. Undergraduate students who major in ecology find it hard to get jobs in China. Most of them now think about career change. But we believe the situation will change in next five years.

How well are ecology grad students paid? What are the hours like? What are your regular duties? (i.e. do you teach, do field work, write papers? etc).

SL: The pay of the students in all the universities of China is very low. For example, in our school, the PhD students could get 1,500 RMB/month [~$250 USD], and the master students could only get 600-800 RMB/month. But the students of Chinese Academy of Sciences could get much more.

In China, most of the graduate students work very hard, from 9:00 am to 5:30 pm in every workday. Sometimes we must work extra hours at night or weekend. I know some of my friends often sleep in their work office. But it depends on the culture of different labs. In my lab, if you could finish your duties on time, you could set your own hours.

Students in my lab do not need to teach, although other students may have to. As a TA, we only need to send messages to the undergrads. Most of a PhD’s time is spend on fieldwork, experiments and paper-writing. Master students do not need to publish papers, so they spend most of their time on doing experiments in the first two years. For the third year, they will spend their time on thesis and finding jobs.

How are research labs structured?

SL: In the labs of our department (School of Life Sciences), we often have one professor (the PI), two or three associate professors, three or four postdoctorates, ten PhD students and 20 master students. We often do not have assistant professors in universities, and it is much easier to become an associate professor in China than in Western countries. Our lab is a little smaller than average; we only have 20 people. Some labs of the famous molecular biologists often have more than 40 students. The biggest lab in our school has about 100 master and PhD students total.

What is your perception of differences between the lab here and the lab you came from?

SL: In China, one big lab often focuses on many different projects. Take our lab for example, we have three different research areas: phytoremediation, environmental microbiology and biodiversity and ecosystem function. The biggest problem is that nobody could understand your research fully except yourself, even your supervisor. If you have any technological or statistical question, you must search for the books or papers by yourself, and it often takes us a lot of time to find the suitable methods and learn how to use them. But in lab here, many of us focus on phylogenetic ecology. If I have any problem, I could discuss it with Marc, you and Lanna [another graduate student] directly. It saved me a lot of time and I can pay more attention to the scientific question, not the technology.

Another difference is the relationship between the students and the professors. In China, the supervisor plays a role as a father, sometimes he is very kindly and sometimes he is very critical. Most of students are afraid of their supervisors. But here, we are all friends and the lab is like a big family. [CT-This may vary among western labs...] One noticeable phenomenon is that there are more excellent female ecologists in western countries. In China, it is very stressful for a girl to become a PhD student because of the traditional culture, especially in ecology.

Are English-language journals available to students? When you publish, is it in Chinese journals, English journals, or a mixture? Is it considered better to publish in international journals?

SL: Most of the English journals are available in Sun Yat-sen University. I think it is not a problem for the top 50 universities in China. However, for small universities and colleges, it may be very difficult for them to download English papers.

Most of the professors do not encourage students to publish papers in Chinese journals. If you only publish papers on Chinese journals, you will not get a good position after you graduate. Instead, publishing papers in international journals is very important for our academic career. If anyone could publish one research paper in Science or Nature, he may be able to get an associate professor position in any universities in China, even full professor position in some universities. However, some of the famous Chinese ecologists publish review papers in Chinese journals to introduce recent international advances, which is a good thing for our young students.

What are the requirements for finishing your PhD? How long will it usually take?

SL: Every student needs to publish at least one paper in any international journals listed on the Web of Knowledge to get their PhD degree. In some departments of our university, you must publish a paper in top journals with an impact factor higher than 3 or 5. We also need to write a thesis and pass the defence. But the thesis is not as important as the paper. I have never seen anyone who published a SCI paper cannot pass the defence. It takes us about 5 years totally to get a PhD degree. If you already have a master’s degree, it only takes you three years. But if you cannot publish a SCI paper on time, you can only get the degree after your paper is accepted. Half of PhD students in our department could not get their degree on time. Most of them would spend one or two years more to wait for the final acceptance for the paper (This is why Chinese scientists often want to urge the editors to deal with their papers as soon as possible). If you cannot publish any paper in your seventh year, you cannot get your degree anymore.

How important is mathematics in ecology in China? Are students expected to have a strong background in it?

SL: All Chinese students have a strong background in mathematics, except for statistics. I think the weak background in statistics is the second biggest problem for ecology students in China (The first one is English). Most of us have not learned statistics comprehensively. If we want to learn some methods of advanced biometrics, we need to read the obscure statistics books. Then we still cannot understand quite well. Most of our students want to learn more about statistics. Last year, Prof. Fangliang He, then at University of Alberta, ran a course named Advanced Biometrics in our university. More than 50 PhD students from 10 different universities came to our university to take this class. Few professors and students focus on theoretical ecology. Instead, most students want to know some advanced skills to deal with their experimental data.

What is doing fieldwork in China like?

In my opinion, we do much more fieldwork than the students of North American universities. I have spent most of my time on grassland experiments and fixed plots experiments in natural reserves. Sometime we even live in a tent on the top of the mountain for several days to collect specimens. The fieldwork in China is often very heavy. I also know that one PhD student who built up 100 fixed plots all over the China by herself.

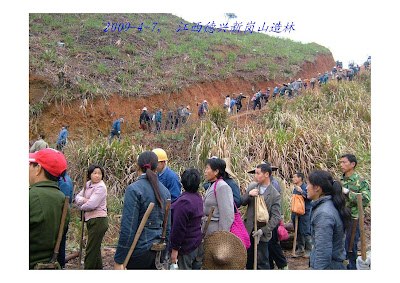

For most of the time, if it is available, we often hire a lot of laborers to help us do the fieldwork. Chinese farmers are very kind and professional. They do the fieldwork much better than our students. Hiring laborers is very cheap in China, and this is why we could do a lot of big projects that the western ecologists may not be able do.

|

| A large-scale biodiversity and ecosystem function experiment. The people in the picture are hired labourers who do the fieldwork. http://www.bef-china.de/index.php/en/ |

SL: Recently, the development of science in China is very fast, with more and more Chinese scientists publishing high impact papers in international journals. I think there are many reasons. First, Chinese government is paying more and more attentions and money to scientific research, especially the hot topics such as climatic change, biological invasion and environmental pollution. The total investment of research funds was approximately one trillion in 2012 in China. Second, we have the largest number of researchers and PhD students all over the world. The number is still increased very quickly. Third, more and more ethnic Chinese (even non-ethnic Chinese) scientists would like to come back to work in China, which greatly narrowed the gap of research capabilities between China and western countries. In the area of ecology, the international communication and the ethnic Chinese ecologists in western countries contribute a lot to the development of ecology in China. More and more Chinese scientists want to interact with western ecologists. And 80% of the papers published by Chinese have foreign co-authors, who often help them to improve the language and statistical analysis.

However, there are still many problems in our science research. In my opinion, the lack of creative and critical thinking is the biggest problem in recent Chinese science. Most of the time, we are just following the hot topics. For ecology, there are few new theories or hypothesis created by Chinese ecologists. Instead, we like to do a lot of work on long-term and large scales experiments to test the recent hot topics. We spend more money and labor force on research projects, but often publish papers of lower qualities. There are many big project at large scales in China. For example, we have about 15 plots in the Center for Tropical Forest Science (CTFS) system, each 5-30ha. The Chinese Ecosystem Research Network (CERN) also consists of 36 field research stations all over the nation. Few Chinese ecologists focus on theoretical ecology and ecological modeling. Personally, I want to see more work with a basis in well-defined hypothesis and clever experiment design.

Are the ecological topics that are popular in China similar to those that are popular in North America? Is there more or less of a focus on ecological applications, or is basic research also very common there?

SL: I think the three most popular ecological topics in China are: climatic change, biological invasion and the causes and consequences of biodiversity. Most of us focus on the hot topics that are popular in North America (also easy to publish papers in good journals). Our discipline is not comprehensive as North America. Many of the traditional sciences such as taxonomy are dying out.

A lot of ecologists focus on ecological applications in China. Environmental Engineering, restoration ecology and phytoremediation are always hot topics in China because of the serious environmental problems. The ecologists focusing on applications are more popular in newspapers and TV. But doing basic research often has more academic influence.

What is the government doing to encourage scientists to stay in China or come back to China from overseas?

SL: The Chinese government has done a lot of things to encourage oversea scientists come back to China. For example, in December, 2008, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party made a decision to have high-level talents (full professor) from overseas come to work in China. Every one could get a lump-sum subsidy of 1 million RMB [~$160,000 USD] and a research subsidy ranging from 3 to 5 million RMB [~$0.5 million USD]. They proposed the “1000-talent Plan”. There are a total of 2,263 registered by July 2012. They also have sub-programs for the young researchers (postdoctorate and assistant professor) and non-ethnic Chinese experts. These subsidies are much higher than the income of native professors. There are many policies that favor scientists from overseas. Advertised positions of Chinese universities often ask for overseas research experiences and papers on top journals.

In contrast, the life of young scientists who stay in China seems very miserable. The subsidies for PhD students, post-doctorates and associate professors are much much less, although they can vary. More importantly, you could not find a good position because you do not have “overseas research experiences” and high-quality papers. This is why more and more young people in China want to study abroad. The government does also encourages young scientists to study abroad. Every year, China Scholarship Council (CSC) supports more than 10,000 students to study abroad as full or visiting PhD students. For example, I am a visiting PhD supported by CSC, and my scholarship covers all the international airfare and my living stipend in Canada for one year.

|

| Students from Shaopeng's lab in the field. Shaopeng is second from the right. |

Edited 4:00 pm EST, April 15 2013.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)