Some places are more valuable than others. We often regard

places as being of high or unique value if they possess high biological

diversity, ancient cultural artefacts and structures, or outstanding geological

features. These valuable places deserve special recognition and protection. The

sad reality is that when we are driven by immediate needs and desires, these

special places are lost.

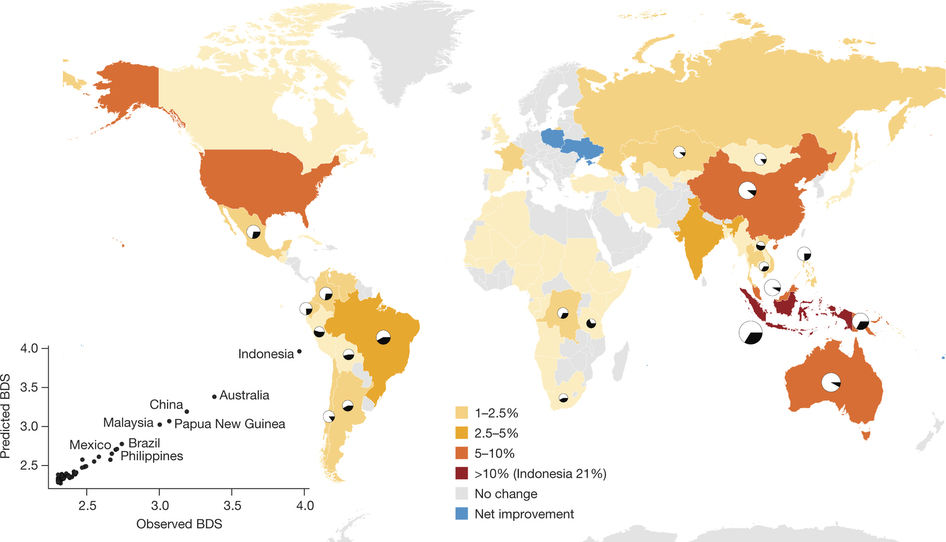

The natural world, and the wonderful diversity of plants and

animals, is on the losing end of a long and undiminished conflict with human

population growth, development, and resource extraction. We don’t notice it

when there is ample natural space, but as nature becomes increasingly relegated

to a few remaining places, we place a high value on them.

The same can be said for places with significant cultural

value. Ancient temples, villages, and human achievement are too valuable to

lose and we often only have a few remnants to connect us to the past.

In either case, natural or cultural, when they’re gone, we

lose a part of us. That is because these special places tell us about

ourselves; where we come from, how the world shaped us, and what unites all of

humanity. Why did the world cry out in a united voice when the

Taliban destroyed the Buddhas of Bamiyan in 2001, even though many of those concerned people were not Buddhist?

The answer is simple –the expansion of Buddhism out of India along ancient

trade routes tells us why many Asian nations share a common religion. They tell

us about ourselves, the differences that interest us, and the similarities that

bind us. The same can be said about the global outcry over the recent

destruction of the ancient city of Palmyra by ISIS.

|

| Before and after photos of the taller of the Buddhas of Bamiyan. Image posted by Carl Montgomery CC BY-SA 3.0. |

Similarly, the natural world tells us about ourselves. The

natural world has constantly shaped and influenced what it means to be human.

Our desires, fears, and how we interact with the natural world are products of

our evolution. If I flash a picture of a car to my 500-student ecology class,

very few students, if any, screech in fear. But if I flash a photo of a hissing

cobra or close-up of a spider, invariably a bunch of students squirm, gasp, or scream. Rationally, this is an odd response, since cars are

the leading cause of death and injury in many western countries. Snakes

and spiders kill very few people in Canada.

These special places deserve recognition and protection, and

that is what the

UNESCO World Heritage designation is meant to achieve. To get this

designation for a site requires that countries nominate ones that represent unique and

globally significant contributions to world heritage, and are adequately

protected to ensure the long-term existence of these sites.

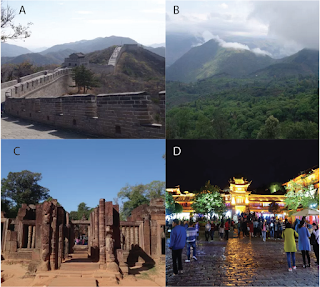

World Heritage sites are amazing places. They

represent the gems of our global shared heritage. They need to be protected in

perpetuity and should be accessible to all people. Though some I have visited

seem like they are loved too much with high visitation rates degrading some elements of

Heritage sites.

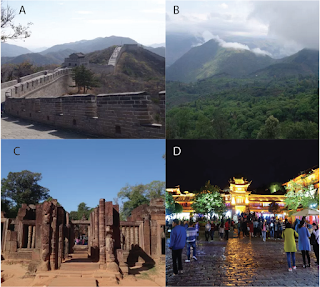

|

| Examples of UNESCO World Heritage sites. A) The Great Wall of China. B) The Gaoligong Mountains, part of the Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan. C) Angkor Wat in Cambodia. D) An example of a site that may be too loved -Lijiang in Yunnan. All photos by Shirley Lo-Cadotte and posted on our family travel blog -All The Pretty Places. |

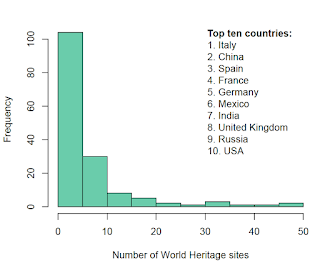

UNESCO World Heritage sites should also be representative.

What I mean by this is that they should be designated regardless of national

borders. Heritage sites are found on all continents across most countries

–though a number of politically unstable countries (e.g., Liberia, Somalia,

etc.) do not possess Heritage sites, likely because they lack the organization

or resources to undertake the designation application process, and they lack

the governance to ensure a site is adequately protected. But there are

substantial differences in the number of World Heritage sites across nations

[1]. Some

countries, because of inherent priorities, national pride, resources or

expertise, are better able to identify and persuade UNESCO that a particular

place deserves designation.

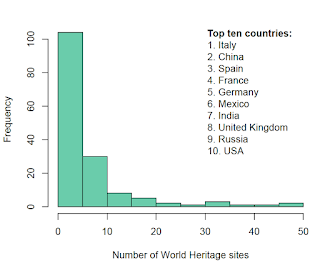

|

| The distribution of the number of UNESCO World Heritage sites across countries and the top ten. |

Why do we see such disparity in the number of World Heritage

sites -where many countries have few sites, and a few countries have many sites? This is a difficult question to answer, and to do so I took an empirical

approach. I combined data on the number of sites per country with Gross

Domestic Product (GDP)

[2],

country size

[3],

and country population size

[4]. I

then ran simple statistical analyses to figure out what predicts the number of Heritage

sites, and identified those countries that are greatly over-represented by Heritage

sites, and those that are very under-represented. A couple things to note, the

best statistical models included variables that were all log-transformed, I

excluded the World Heritage sites that spanned more than one country, and I did

not include countries that did not have any Heritage sites. The data and R code have been

posted to Figshare and are freely available.

All three of GDP, area, and population size predicted the

number of World Heritage sites. It is important to note that these three

country measures are not strongly correlated with one another (only moderately

so). So, larger, richer and more populous countries had more World Heritage

sites. This makes sense –big countries should contain more unique sites due to

random chance and more populous countries tend to have longer historical presence of organized states, and so should

possess more cultural relics (especially China). GDP is more difficult to assign a reason, but high GDP countries should have robust national parks or other bureaucratic

structures that assess and protect important sites, making them easier to

document and justify for UNESCO. GDP is

quite interesting, because it is the single best measure for predicting the

number of Heritage sites, better than population size and area. Further, neither

country density (population/area) nor productivity (GDP/population) are strong

predictors of the number of Heritage sites.

|

| The relationships between the number of World Heritage sites and GDP, area, and population. Note that the axes are all log-transformed. |

While these relationships make sense, it is also clear that

countries are not all close to the main regression line and some countries are

well above the line –meaning they have more Heritage sites than predicted; as

well as some below the line and thus having fewer sites. When I combine the different

measures in different combinations and look for the best single statistical

explanation for the number of World Heritage sites, I find that the combination

including GDP and population size, and their interaction (meaning that

population size is more important for high GDP countries) is the best. For

aficionados, this model explains about 65% of the variation in the number of

Heritage sites.

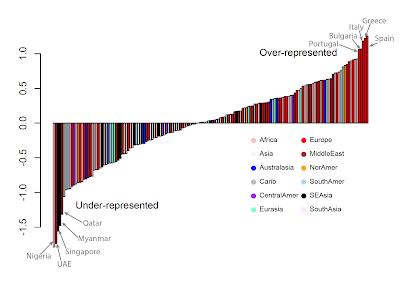

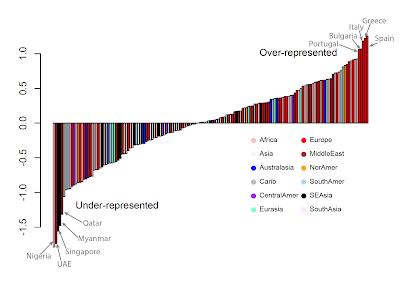

Now, we can identify those countries that are over or under

represented by UNESCO World Heritage sites according to how far above or below

countries are from the predicted line (technically, looking at statistical

residuals).

|

| The deviation of countries from the predicted relationship between the number of sites and GDP and population (and their interaction). The top 5 over-represented and under-represented countries are highlighted. |

The top five over-represented countries are all European,

which means that given their GDP and population size, these countries have more

World Heritage sites than expected. At the other extreme, countries

under-represented come from more diverse regions including Africa, the Middle

East and Southeast Asia.

An interesting comparison to think about is Germany and

Indonesia. Germany has more World Heritage sites than expected (residual =

+0.61) and is a moderately sized, high GDP country. Let me say, I like Germany,

I’ve been there a half a dozen times, and it has beautiful landscapes and great

culture. However, does it deserve so much more World Heritage recognition than

Indonesia, which has fewer sites than expected (residual = -0.63)? Indonesia

has spectacular landscapes and immense biodiversity and great cultural

diversity and history. To put it in perspective, Germany has 35 World Heritage

sites and Indonesia has just 8.

To answer the question in the title of this post: what’s so

great about Spain? Well, it not only has beautiful and diverse natural landscapes

and cultural history, but it appears to have the infrastructure in place to

identify and protect these sites. It's place at the top of UNESCOs relative (to

GDP and population) ranking of the number of World Heritage sites means that Spain's natural and cultural wonders are in good hands. However, for the countries

at the other end of the spectrum, having relatively few World Heritage sites probably is not a reflection of these countries being uninteresting, or that they have

little to offer the world, rather it is something more alarming. These places

lack the financial capacity or national will to fully recognize those places

that are of value to the whole world. The problem is that the globally

important heritage that does exist in these places is at risk of being

lost. These under-represented countries serve as a call to the whole world to

help countries not just identify and protect heritage sites but to aid these

countries with infrastructure and human well-being that empowers them to

prioritize their natural and cultural heritage.