|

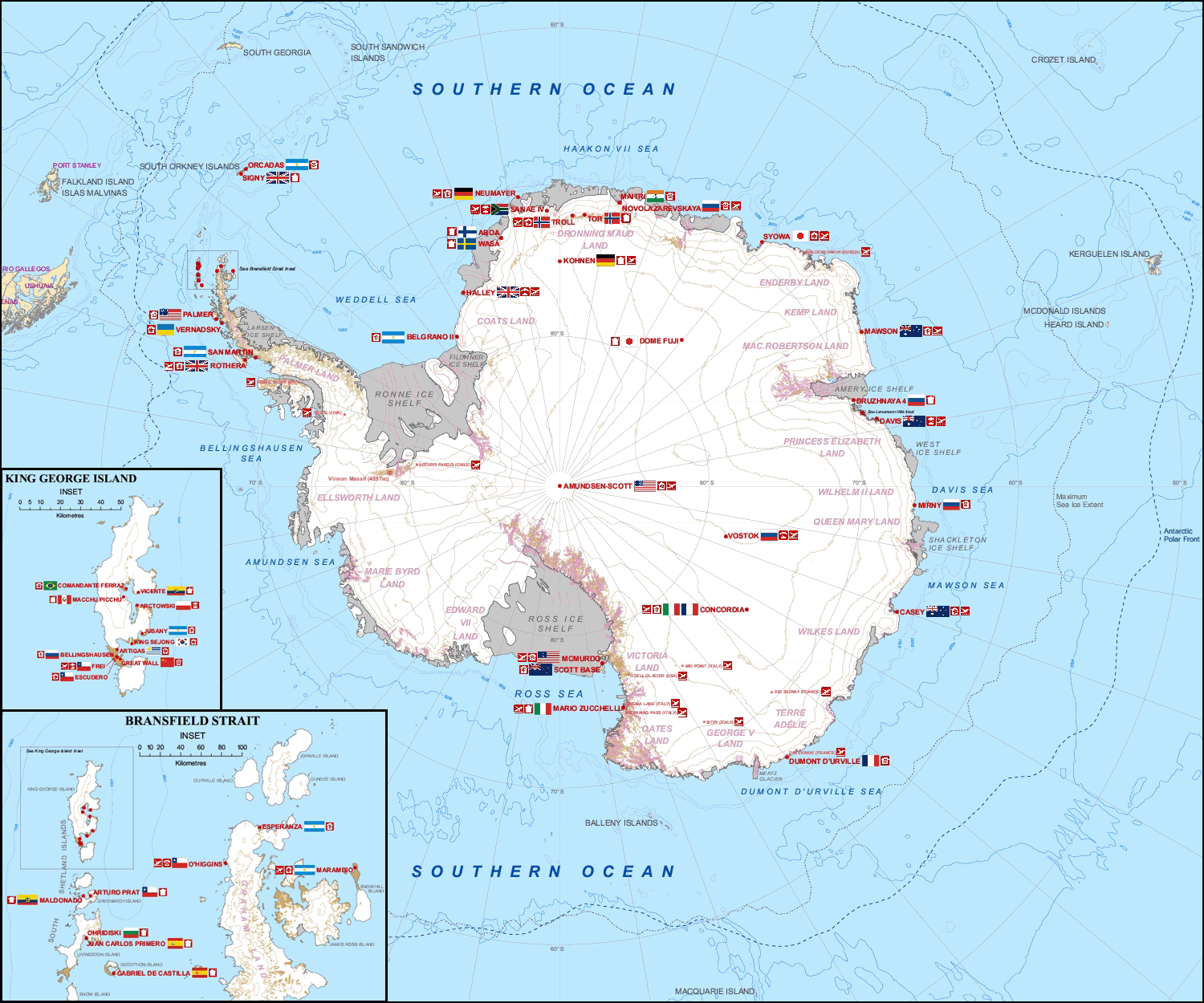

| Location of Antarctic field stations. Image from Wikipedia. |

Field ecology is difficult, time-consuming and expensive. Ecologists need to make decisions about where to do research, and if research questions focus on remote locations, there are likely a lot of constraints limiting options. For example, if research requires work in the Antarctic, odds are you'll be working at one of a few locations on the coast which, depending on the nature of the research, could bias our understanding of ecological or geological processes operating there.

The research needed for some questions can literally occur almost anywhere without much worry about how local context biases findings. That's not to say that local context will not play a role in ecological dynamics, and we should always be mindful of how local conditions influence the processes we are interested in. However, some questions are sufficiently general that we could envisage running an experiment in our backyard. However, there are research questions that necessitate careful consideration of the geographical location of research.

This is especially true for questions that pertain to the consequences of environmental change on ecological systems. The drivers of environmental change, whether it be pollution, nutrient deposition, changing temperature, extreme weather events or changes in precipitation patterns, all vary across the Earth and their impacts are similarly unequal. We shouldn't expect that a 2 degree C increase in average temperature to have the same effect in the tropics as, say, the arctic.

|

| Location of Nutrient Network sites used in Borer et al. 2014 |

This issue of the geography of research biasing our understanding of the impacts of global change is especially true for understanding the consequences of climate change in the Arctic. This was highlighted superbly by Metcalfe and colleagues recently (Metcalfe et al. 2018). They showed that most of the terrestrial ecology research in the Arctic has occurred in just a few places. And while this work has been extremely impactful and important for understanding the ecology of Arctic systems, they are not located in places undergoing the most drastic changes in climate. Therefore, because of the geographical location of research, we might not have a very good understanding of the impacts of climate change on Arctic ecosystems.

|

| Where research is being done in the Arctic. Panel 'a' shows where publications are coming from and 'b' shows the impact in terms of number of citations (from Metcalfe et al. 2018). |

| ||

| This shows where photosynthesis has changed the most, which does not correspond well to where the research has been done (from Metcalfe et al. 2018). |

This type of mismatch in climate change and research requires that ecologists purposefully establish research sites in areas that are rapidly changing. Metcalfe and colleagues suggest that the governments of Arctic nations establish focused research funding to support and promote research in these regions. This of course requires government dedication. The reality is it is cheaper and more efficient to do more research in existing, well supplied, field stations. Arctic scientists and professional organizations need to lobby environment or research government departments, and this research gap is an opportunity for Arctic governments to cooperate and share research costs.

References

Adler, P. B., E. W. Seabloom, E. T. Borer, H. Hillebrand, Y. Hautier, A. Hector, W. S. Harpole, L. R. O’Halloran, J. B. Grace, T. M. Anderson, J. D. Bakker, L. A. Biederman, C. S. Brown, Y. M. Buckley, L. B. Calabrese, C.-J. Chu, E. E. Cleland, S. L. Collins, K. L. Cottingham, M. J. Crawley, E. I. Damschen, K. F. Davies, N. M. DeCrappeo, P. A. Fay, J. Firn, P. Frater, E. I. Gasarch, D. S. Gruner, N. Hagenah, J. Hille Ris Lambers, H. Humphries, V. L. Jin, A. D. Kay, K. P. Kirkman, J. A. Klein, J. M. H. Knops, K. J. La Pierre, J. G. Lambrinos, W. Li, A. S. MacDougall, R. L. McCulley, B. A. Melbourne, C. E. Mitchell, J. L. Moore, J. W. Morgan, B. Mortensen, J. L. Orrock, S. M. Prober, D. A. Pyke, A. C. Risch, M. Schuetz, M. D. Smith, C. J. Stevens, L. L. Sullivan, G. Wang, P. D. Wragg, J. P. Wright, and L. H. Yang. 2011. Productivity Is a Poor Predictor of Plant Species Richness. Science 333:1750-1753.

Borer, E. T., E. W. Seabloom, D. S. Gruner, W. S. Harpole, H. Hillebrand, E. M. Lind, P. B. Adler, J. Alberti, T. M. Anderson, J. D. Bakker, L. Biederman, D. Blumenthal, C. S. Brown, L. A. Brudvig, Y. M. Buckley, M. Cadotte, C. Chu, E. E. Cleland, M. J. Crawley, P. Daleo, E. I. Damschen, K. F. Davies, N. M. DeCrappeo, G. Du, J. Firn, Y. Hautier, R. W. Heckman, A. Hector, J. HilleRisLambers, O. Iribarne, J. A. Klein, J. M. H. Knops, K. J. La Pierre, A. D. B. Leakey, W. Li, A. S. MacDougall, R. L. McCulley, B. A. Melbourne, C. E. Mitchell, J. L. Moore, B. Mortensen, L. R. O'Halloran, J. L. Orrock, J. Pascual, S. M. Prober, D. A. Pyke, A. C. Risch, M. Schuetz, M. D. Smith, C. J. Stevens, L. L. Sullivan, R. J. Williams, P. D. Wragg, J. P. Wright, and L. H. Yang. 2014. Herbivores and nutrients control grassland plant diversity via light limitation. Nature 508:517-520.

Metcalfe, D. B., T. D. Hermans, J. Ahlstrand, M. Becker, M. Berggren, R. G. Björk, M. P. Björkman, D. Blok, N. Chaudhary, C. J. N. e. Chisholm, and evolution. 2018. Patchy field sampling biases understanding of climate change impacts across the Arctic. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2:1443.

Seabloom, E. W., E. T. Borer, Y. M. Buckley, E. E. Cleland, K. F. Davies, J. Firn, W. S. Harpole, Y. Hautier, E. M. Lind, A. S. MacDougall, J. L. Orrock, S. M. Prober, P. B. Adler, T. M. Anderson, J. D. Bakker, L. A. Biederman, D. M. Blumenthal, C. S. Brown, L. A. Brudvig, M. Cadotte, C. Chu, K. L. Cottingham, M. J. Crawley, E. I. Damschen, C. M. Dantonio, N. M. DeCrappeo, G. Du, P. A. Fay, P. Frater, D. S. Gruner, N. Hagenah, A. Hector, H. Hillebrand, K. S. Hofmockel, H. C. Humphries, V. L. Jin, A. Kay, K. P. Kirkman, J. A. Klein, J. M. H. Knops, K. J. La Pierre, L. Ladwig, J. G. Lambrinos, Q. Li, W. Li, R. Marushia, R. L. McCulley, B. A. Melbourne, C. E. Mitchell, J. L. Moore, J. Morgan, B. Mortensen, L. R. O'Halloran, D. A. Pyke, A. C. Risch, M. Sankaran, M. Schuetz, A. Simonsen, M. D. Smith, C. J. Stevens, L. Sullivan, E. Wolkovich, P. D. Wragg, J. Wright, and L. Yang. 2015. Plant species' origin predicts dominance and response to nutrient enrichment and herbivores in global grasslands. Nat Commun 6.

No comments:

Post a Comment