For example, macroevolutionary hypotheses are generally only testable using observational data. They suffer from the obvious problem that they generally relate to processes of speciation and extinction that occurred millions of years ago. The exception is the case of short generation, fast evolving microcosms, in which experimental macroevolution is actually possible. Which makes them really cool :-) In a new paper, Jiaqui Tan, Xian Yang and Lin Jiang showing that “Species ecological similarity modulates the importance of colonization history for adaptive radiation”. The question of how ecological factors such as competition and predation impact evolutionary processes such as the rapid diversification of a lineage (adaptive radiation) is an important one, but generally difficult to address (Nuismer & Harmon, 2015; Gillespie, 2004). Species that arrive to a new site will experience particular abiotic and biotic conditions that in turn may alter the likelihood that adaptive radiation will occur. Potentially, arriving early—before competitors are present—could maximize opportunities for usage of niche space and so allow adaptive radiation. Arriving later, once competitors are established, might suppress adaptive radiation.

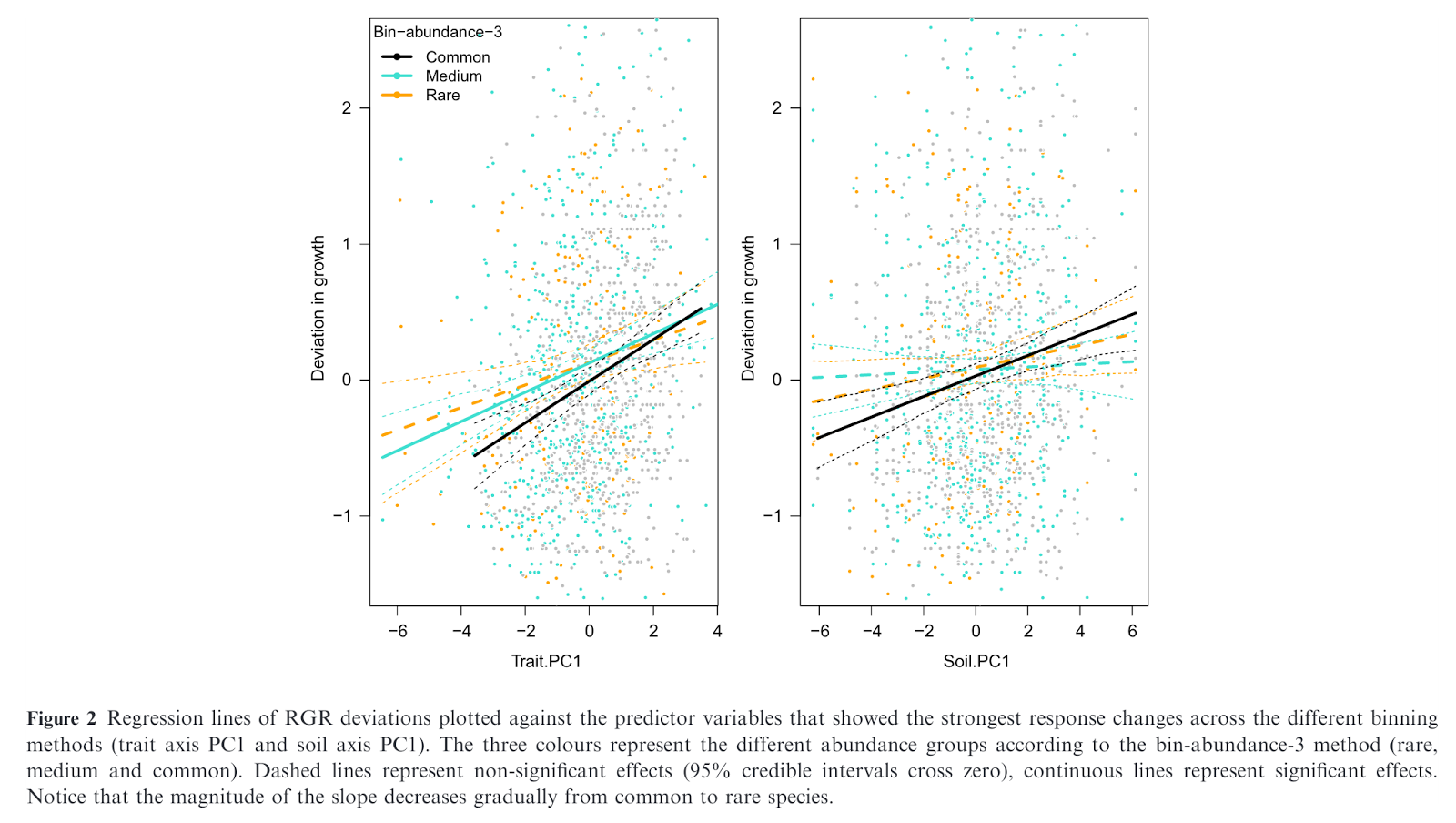

More realistically, arrival order will interact with resident composition, and so the effects of arriving earlier or later are modified by the identities of the other species present in a site. After all, competitors may use similar resources, and compete less, or have greater resource usage and so compete more. Although hypotheses regarding adaptive radiation are often phrased in terms of a vague ‘niche space’, they might better be phrased in terms of niche differences and fitness differences. Under such a framework, simply having species present or not present at a site does not provide information about the amount of niche overlap. Using coexistence theory, Tan et al. produced a set of hypotheses predicting when adaptive radiation should be expected, given the biotic composition of the site (Figure below). In particular, they predicted that colonization history (order of arrival) would be less important in cases where species present interacted very little. Equally, when species had large fitness differences, they predicted that one species would suppress the other, and the order in which they arrived would be immaterial.

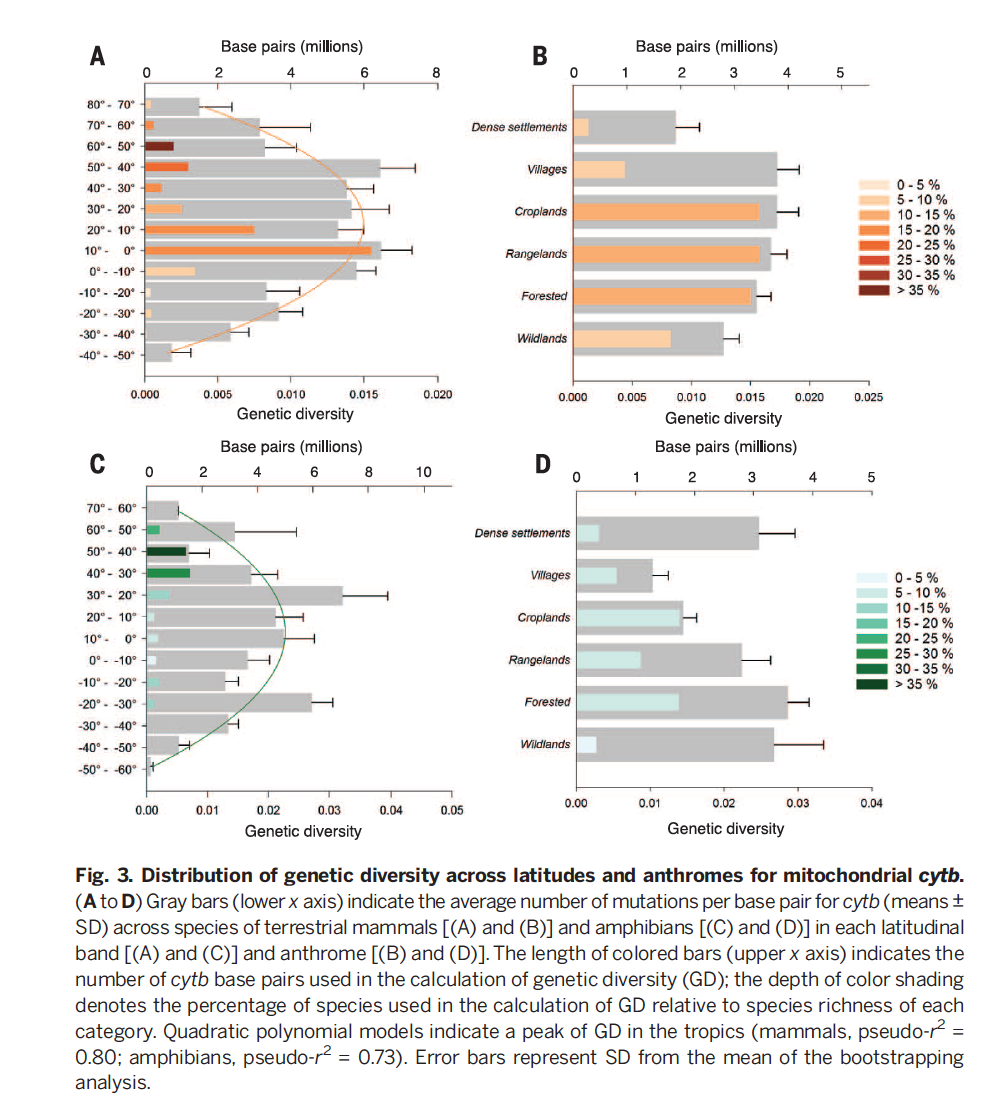

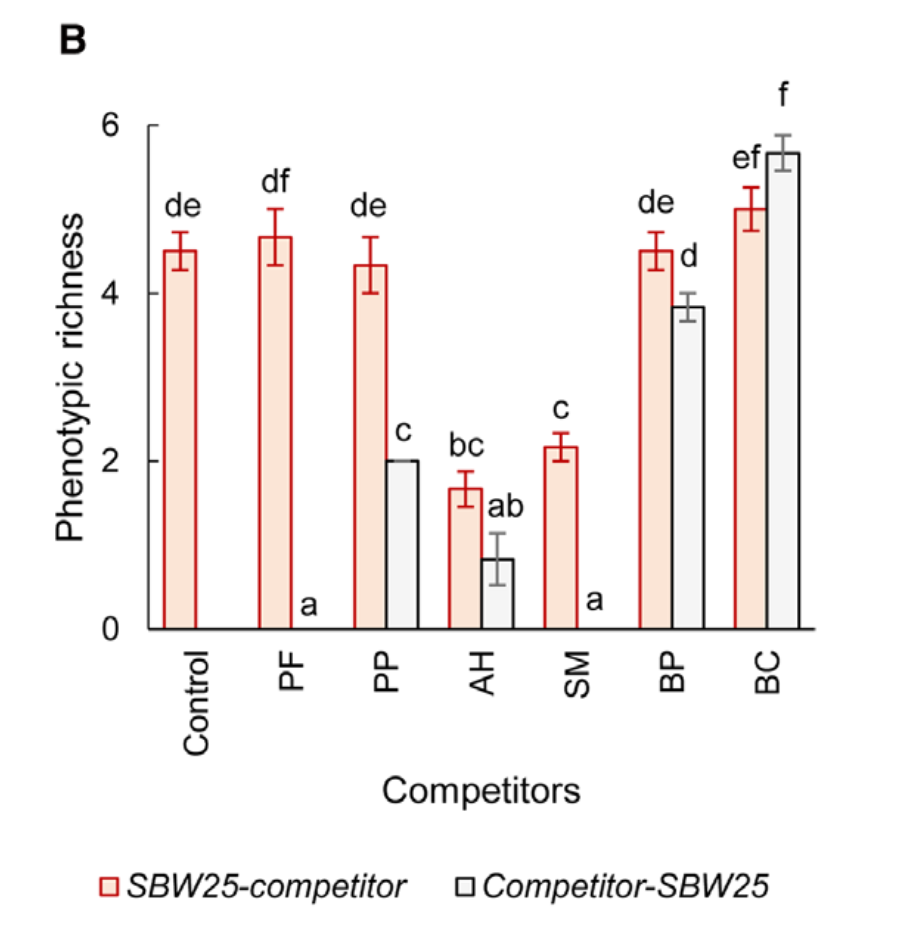

The authors tested this using a bacterial microcosm with 6 bacterial competitors and a focal species – Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25. SBW25 is known for its rapid evolution, which can produce genetically distinct phenotypes. Microcosm patches contained 2 species, SBW25 and one competitor species, and their order of arrival was varied. After 12 days, the phenotypic richness of SBW25 was measured in all replicates.

Both order of arrival and the identity of the competitor did indeed matter as predictors of final phenotypic richness (i.e. adaptive radiation) of SBW25. Further, these two variables interacted to significantly. Arrival order was most important when the 2 species were strong competitors (similar niche and fitness differences), in which case late arrival of SBW25 suppressed its radiation. On the other hand, when species interact weakly, arrival order had little affect on radiation. The effect of different interactions were not entirely simple, but particularly interesting to me was that fitness differences, rather than niche differences, often had important effects (see Figure below). The move away from considering the adaptive radiation hypothesis in terms of niche space, and restating it more precisely, here allowed important insights into the underlying mechanisms. Especially as researchers are developing more complex models of macroevolution, which incorporate factors such as evolution, having this kind of data available to inform them is really important.

The authors tested this using a bacterial microcosm with 6 bacterial competitors and a focal species – Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25. SBW25 is known for its rapid evolution, which can produce genetically distinct phenotypes. Microcosm patches contained 2 species, SBW25 and one competitor species, and their order of arrival was varied. After 12 days, the phenotypic richness of SBW25 was measured in all replicates.

|

| From Tan et al. 2017. Competitor order of arrival in general altered the final phenotypic richness of SBW25. |

|

| Interaction between final phenotype richness and arrival order for B) niche differences and D) fitness differences. S-C refers to arrival of SWB25 first, C-S refers to its later arrival. |